A language will tend to assign shorter words to more common concepts. To put it another way, the shorter words in a language point us towards what its culture views as most important.

In Japanese, all verbs end in U. It’s one of the many remarkably symmetric and regular aspects of the language. In terms of hiragana syllables, it’s U, or KU, or SU, or TSU, or NU, or MU, or RU (lots of those). There is no verb ending in HU, YU, or WU.

So we hypothesize that the common concepts in the Japanese worldview are going to be the possible shortest verbs, ones of two syllables: any of the 46 standard syllables (or 44 if you omit ん and を), followed by one of these eight syllables from the U column of the table of fifty syllables. But we also have GU (think nugu), and BU (think tobu). So there are several hundred possible combinations. How many of these actually exist? In other words, how tightly is this space packed with real words? Encoding theory predicts that from the standpoint of redundancy and error corrections, the encoding should not be too packed.

う (u)

Let’s start off by looking at the verbs where the second syllable is U.

A number of interesting things pop out. First, out of the 50 possible combinations, only 13 are actually used. So our hypothesis about the low density of word assignments (about a quarter in this case) is borne out. Also, there were no words whatsoever in the R-row (non-existent words like RAU), nor any in the E-column (non-existent words like KEU). In fact, those turn out to be rules that apply to native Japanese word formation in general, with a few exceptions.

A student of Japanese could do far worse that start off by learning these basic, two-syllable words (and, of course, how to conjugate them if you haven’t mastered that yet). Then you could go from there by finding related words such as nawa (rope, from nau), to take just one example of many. Might work better than flash cards.

Today’s thought question: What do all these native Japanese verbs ending in -U have in common, meaning-wise? Are there any meaning patterns along the rows, or columns? Could it be that the first column, containing verbs of the form XA-U, are all about interacting and moving back and forth?

く (ku)

Let’s move on to two-syllable native Japanese words ending in -KU. Do you think there will be more of these?

Look at that. The A-column is completely full. The U-column is nearly full, missing only KUKU. We can hypothesize a rule where syllables are not repeated—in the U version, for instance, there was no verb UU, nor are there verbs SUSU, or TSUTSU, or NUNU. The density of this -KU table has risen to almost 50%. If we omit the E-column and the R-row from the calculation, it’s over 60%.

す (su)

What about two-syllable Japanese verbs ending in SU?

About 20% of all the possible two-syllable verbs ending in -SU actually exist. We have our first verb with a first syllable from the E-column (kesu).

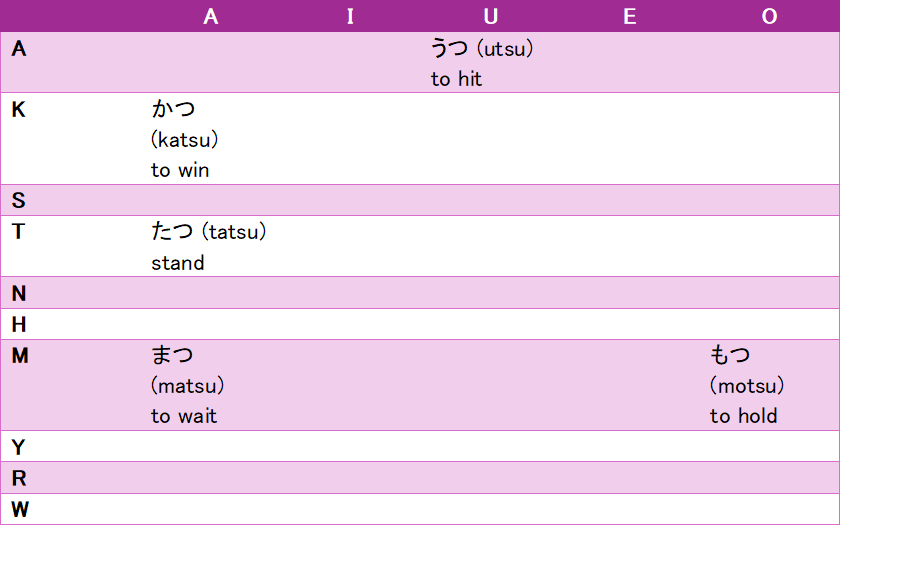

つ (tsu)

Next up is TSU.

Many of these -TSU verbs are very high-frequency, but overall only 10% of the possible two-syllable verbs actually exist.

Moving forward

This has been so much fun that we will continue in future posts with the other rows of the 50-syllable table, including -NU (of which actually there is just one verb, namely shinu), -MU, -RU. There are no verbs ending in -FU, or -YU.

For purposes of completeness, we should extend this analysis to indicate verbs from classical Japanese. There are also cells in our tables which have strong semantic associations but are not actual words in and of themselves—such as HAMU, from which HAMERU and HAMARU are derived, or ATSU, at the base or ATSUMERU and ATSUMARU.

And finally we should point out that this entire exercise has focused on so-called GODAN verbs, sometimes called う (u)-verbs in textbooks. We can do another, similar analysis for ICHIDAN verbs, sometimes called る (ru)-verbs, like neru.

Fascinating and very helpful for learning frequent Japanese verbs. Please would you consider including the kanji spelling in the tables?

This was so interesting. I’ve never considered Japanese verbs in this way.