The Japanese word "o” means “tail”.

Out of only forty-some single-syllable words to assign meanings to, ancient Japanese decided that “tail”/o was one of the most important ones!

That’s because, like so many other Japanese words, o can actually be used for a wide variety of things. Besides your cat’s furry tail, it can mean the end of almost anything—the “tail end” of something, if you will.

Most likely the sound o was chosen for “tail” because your mouth stretches out like a tail when you make it. Try it! That’s an example of the phenomenon called “oral iconicity” or “articulatory iconicity”. These are your words of the day.

And this word also has a ubiquitous verbal form, meaning “end”: owaru, literally “to tail off”.

Chinese Character

When the time came to decide which kanji to assign to o, the choice was obvious: 尾.

The character 尾 is a phono-semantic compound, like so many others. This means it's made up of two parts: one that gives a clue to the meaning (the semantic component) and one that gives a clue to the pronunciation (the phonetic component).

In the case of 尾, it's composed of:

尸: This is the semantic component. It originally depicts a person lying down on their side, maybe with their legs crossed.

毛: This is the phonetic component. It means "fur" or "hair”. Originally, it provided a clue to the ancient Chinese pronunciation, although the modern Japanese readings have diverged significantly

But while 毛 primarily serves as the phonetic part, it also has a strong semantic connection to the meaning of "tail"! The shape of the 毛 component does indeed resemble something like a tail or a tuft of hair. This visual similarity wasn't just a coincidence; it likely influenced the choice of this element. The horizontal lines in 毛are little bits of fur sticking out, and the vertical line is the tail itself, curving down to its end. This blend of phonetic function and visual, semantic reinforcement in the phonetic component itself is a common and natural feature in Chinese character evolution.

Both the Chinese 尾 and the Japanese o at some point extended their meanings to refer to the end part of something, or something ending. In Japanese that took the form of the verb owaru, “to come to an end”, which of course in kanji would be written 尾わる.

Just kidding. Of course it’s 終わる. Once again, it’s almost as if Japanese is trying to conceal the way that its words and concepts are connected.

This word is super-useful in compound verbs (複合動詞) like 食べ終わる (tabe-owaru, finish eating).

It’s worth pointing out that owaru is not necessarily something ending abruptly or suddenly. It can be, and often is, gradual. It can refer to a progressive cessation. It can mean “come to an end”. It can be the process of ending. Of course, the same thing is true of the English word “tail off”.

So both English “tail” and Japanese o have multiple abstract meanings. But English “tail is more generally reserved to concrete things like animals or vehicles (a car’s “taillight”, the “tail of a rocket”, “tailgate”), although it’s also used for the remainder of a list in computer science, or the remainder of a formula in mathematics, or the tail of a comet.

Mountain Tails

But in Japanese, a "tail” can also link to the natural landscape, embodying the the principle of how Japanese links the human body and nature in ways that might feel foreign to English speakers.

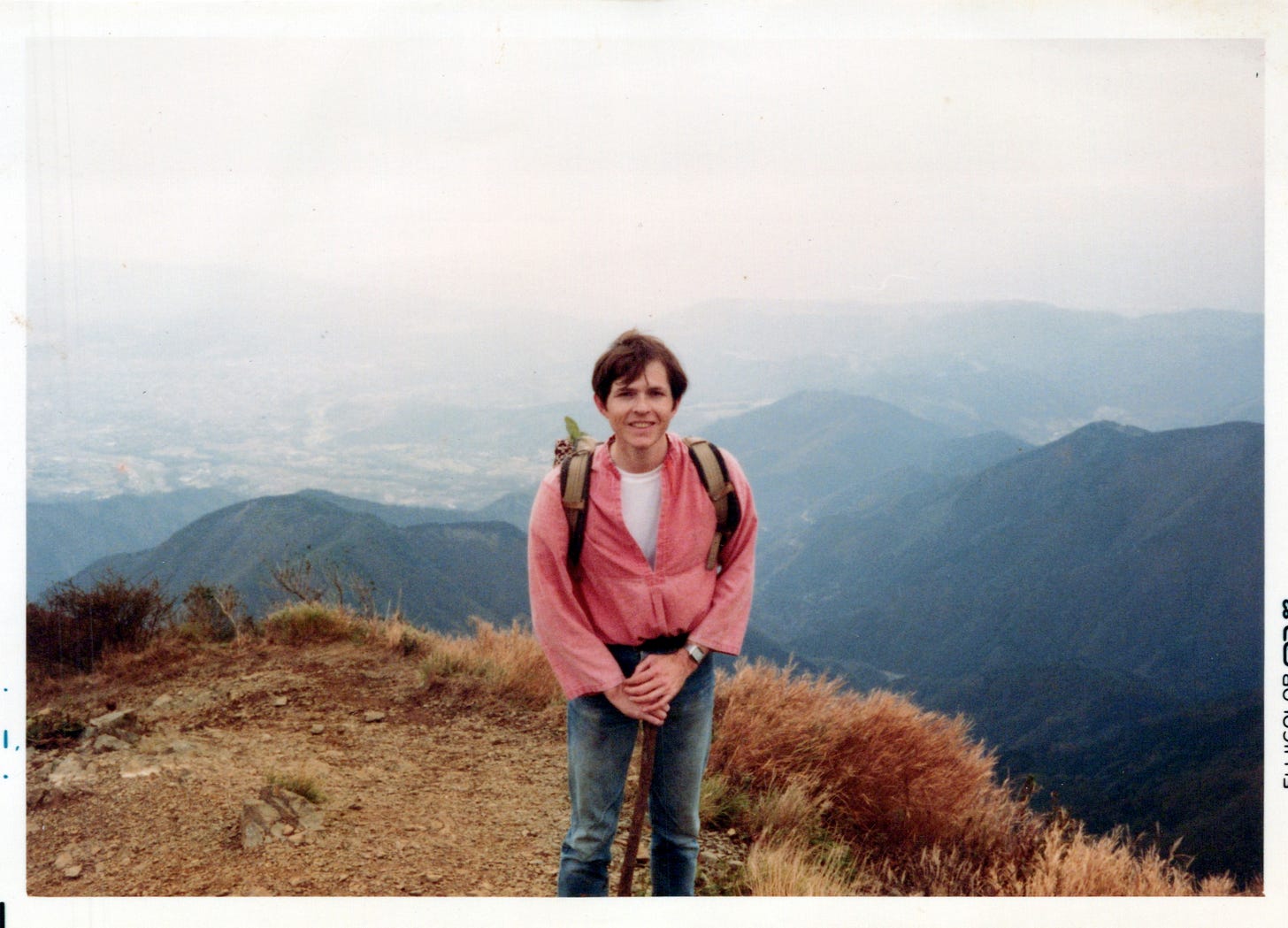

Let's consider Mt. Takao (高尾山, Takao-san). Located on the outskirts of Tokyo, Takao-san is a beloved spot for hiking and a popular weekend getaway. Here’s a familiar gaijin after the grueling 30-minute climb .

The name “Takao” can be understood as "high tail" (高 + 尾). And that’s exactly what it is: it’s a “tail” of the mountain, pointing upwards to the right, shown in the red rectangle. See?

This tendency in Japanese to use body parts—like 尾 (o, tail) and even 尻 (shiri, butt/rear, see below)—for natural phenomena and abstract concepts is a key difference from how English often employs such terms, as we have repeatedly seen, such as in the case of hana.

By the way, you will often encounter Japanese family names with the character 尾. Normally these refer to places. For example, if a farm village had a long, tail-like appendage going off to the west, that might be 西尾 (Nishio) or 長尾 (Nagao), and then that name would have been given to the people living there.

Old Japanese

The verbs owaru and oeru, related to the underlying concept of “tail”, date back to the Heian Period versions 終ふ (ofu), which became modern 終わる, and 終へる (oheru), which became modern 終える (bring to an end). The core idea of ending or finishing was already well-established in these classical forms. The word had even broader connotations than today, such as ”behind”, “end”, or “last one”, extending even to time or sequence, meaning "after" or “last”, or even causality as in “end up as”. This reinforces the idea that “tail” or “rear” concepts in Japanese were more broadly associated with the notion of finality or position than perhaps their English counterparts.

One notable combination of 尾 that you’ll hear a lot is 尻尾 (shippo). This word for “tail” combines 尻 (shiri, butt/rear) and 尾 (o, tail). But how does “shiri” + “o” become “shippo”? It's a bit of a phonetic journey! The “ri” sound from 尻 effectively drops out in the compound. The "o" from 尾, when combined, is treated historically and phonologically as if it had an initial "h" sound (based on kana workings). This implied "h" then undergoes a process called fortition, becoming a stronger consonant, in this case, a "p". This "p" sound is then geminated (doubled), resulting in the “ppo” sound that follows “shi”, giving us 尻尾. This transformation is not rendaku; it's a different phonological process involving fortition and gemination. If you’re in an informal situation, you can use oppo (尾っぽ or おっぽ).

So, next time you hear 尾 (o/bi) remember its layers of meaning. It's not just a word for an animal appendage; it's a concept that extends metaphorically to describe the end of almost anything—including the "tails" of mountain ranges.

Thank you so much for this article! Very informative!