Stopping in Japanese

Stopping is a basic concept in life. How does Japanese handle it? The first word that comes to mind is 止める/tomeru.

Fun fact: this character 止 is the source of both hiragana to (と) and katakana to (ㇳ)! The hiragana derives from a cursive version; the katakana just takes the right part. Here is a hiragana to for your viewing pleasure, from the noted Japanese font designer Keinosuke Sato.

The character 止 depicts a footprint. It’s purely hieroglyphical. The lines pointing up are the toes, as can be seen in the ancient bronze inscription version below.

Of course, these days we use 足 for foot (or leg). If you look closely, the thing on the bottom of that character is basically the character 止. The rectangle on top is a pictogram of a torso, so technically this is a compound pictogram-type kanji. The designers of Chinese characters liked this foot character so much they decided to use it as the left-hand radical ashi-hen for all kinds of concepts related to feet and walking, in the form ⻊. Thought question of the day: how did this character for foot come to mean “suffice” (as in 足りる/tariru)?

But back to 止. Why did a character representing a footprint come to mean “stop”? Theories abound, but possibilities include the fact that footprints are by definition stationary, or that someone is putting their foot down in front of a cart to make it stop, or putting their foot on top of something to keep it from moving.

This character is so basic the Japanese school kids learn it in second grade.

Types of stopping

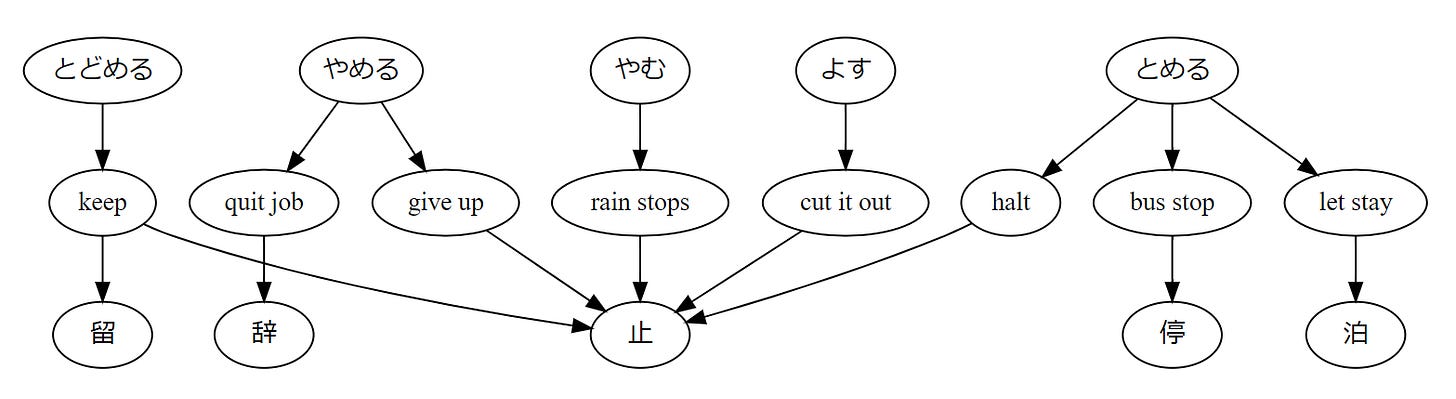

But stopping comes in a variety of flavors. tomeru is about stopping something that is going (or, in the form tomaru, something stopping that had been going). But for something that you yourself are doing (or planning to do), it would be yameru, which could be written with the same character and the same okurigana, so 止める—you’ll have to figure out which one it is from context! Then there is stopping something before it reaches a certain point or a certain level, which is todomeru, which could be written with the same character, once again 止める. If the thing stopping is undesirable, then it could be yamu (止む, for the rain stopping) or yosu (止す, for your kid teasing his little sister).

But to make things even more confusing, there are alternative kanji we can use to write the stopping words like tomeru and todomeru and yameru. For example, todomeru would more commonly be written as 留める. If you’re using tomeru in the sense of giving someone a place to stay, that would be 泊める. If you’re using tomeru to refer to a train or bus stopping, it would be 停める. If you’re using yameru to talk about quitting your job, it would be written as 辞める.

Having trouble keeping all of these straight? Here is a handy reference

Where did words like tomeru and yameru come from, anyway?

Who among us has not wondered about the origin of the words we use everyday? What ancestor of ours dreamed them up? English derives from earlier languages such as Indo-European, but Japanese—in the sense of Yamato-kotoba—has never been shown to have any direct predecessor. It sprang directly from the minds of the ancient Japanese.

One can intuit what must have been most important to the Japanese of old by examining the words which have a single syllable. For instance, i means well; e means picture; o means tail; ki means tree, and so on. Other single-syllable words worthy of note are to, for door or window or gate (now written 戸), and ya for arrow (矢).

My theory is that tomeru is derived from to, and yameru is derived from ya. After all, doors and windows and gates are placed to stop people and things from getting in and out. Stopping something is the equivalent of putting a barrier in front of it in the form of a door or gate. Just say the word to, or tomeru. You can almost hear the gate slamming shut, stopping people from coming in.

For ya, I will leave it up to the reader to imagine the possible relationship with yameru.

Back to Kawabata

So what kind of stopping is going on with the train in Yukiguni that Kawabata characterized as tomatta using the 止まった character? We would expect to see the kanji 停まった for a bus or train making a regularly scheduled stop, normally to take on or let off passengers, so we know that’s not the intent here. To me, this 止まった has a sense of finally stopping, perhaps somewhat suddenly or unexpectedly, or after a long period. That’s just my gut feeling, but a native Japanese informant confirmed this. And in this case it would indeed have been a long period; the previous station would have been Doai (土合), on the Gunma side of the tunnel, and we know the tunnel was 10km long (including two looping, spiral sections!), and since trains back then (a steam train—this stretch was not electrified for several more years) ran at no more than 60kph, it would have been a good 10-minute ride through the tunnel. One almost wants to translate tomatta here as “ground to a halt”, or at least “came to a stop”.

Seidensticker translated this simply as “stopped”, just like every other translator in the world probably would.