The Seven Waterfalls of Kawazu

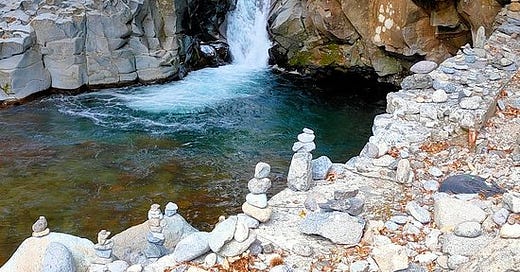

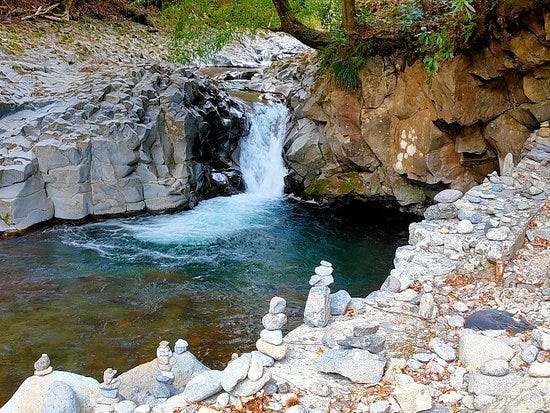

The Kawazu Nanadaru (河津七滝) are a series of seven waterfalls situated in the middle of the Izu Peninsula in Shizuoka, one of my favorite prefectures. They range from the 30m Oodaru (大滝・big waterfall) to the tiny waterfall shown below, Kanidaru (かに滝・crab waterfall, so named because the water has carved a rock on one side into the shape of a crab’s shell), a mere 2m in height.

To get to the seven waterfalls, you will take the JR East Odoriko limited express from Tokyo via Atami. You could get off at Shuzenji, and take the bus to Nanadaru; or go to Kawazu, which is half way down the east coast of Izu, and then take a thirty-minute bus ride up into the mountains. The whole trip should not take much more than three hours. If you’re the onsen type, there’s the Nanadaru Onsen Hotel right there.

Where does the train’s name, Odoriko, come from? As every Japanese knows, this is the dancing girl from the short story “Izu no Odoriko” (“The Dancing Girl of Izu”), written by none other than our old friend KAWABATA Yasunari in 1926, and translated by who else, Edward Seidensticker. The dancing girl is a virginal teen named Kaoru who is essentially stalked by a depressed university student from Tokyo. The story unfolds in the area of the seven waterfalls. There's also a tunnel involved (Amagi-san Tunnel), although this one is short and doesn't cross any provincial boundaries. What's the deal with Kawabata and tunnels?

Waterfalls as taru

Why are these waterfalls called taru, though? I thought waterfalls were 滝/taki?

Actually, there are quite a few waterfalls in this area of Japan, and elsewhere, called taru. It turns out that taru is the original word used for waterfall! It makes sense, when you think of the word 垂れる/tareru, which means to hang or pour or drip down. (That is also the origin of the word tare for “sauce”, derived from the ancient practice of using the drippings from a cloth bag filled with a mixture of miso and water as condiments. But I digress.)

Way back when the word taru was being used for waterfalls, taki was being used for rushing water or other liquids, such a rapids on a river. This is linguistically related to the word tagiru, written 滾る, which means a liquid flowing strongly and turbulently, or water at a rolling boil, or the feeling you have when your blood boils. This is your word of the day!

The signal station

Guess what—the term 樽・たる・taru also appears in the name of the signal stop in the third sentence of Kawabata’s Snow Country, which is named 土樽・Tsuchitaru, although he did not mention the name.

This signal stop was located no more than a few hundred yards from the tunnel exit. Its purpose was to let trains going in the other direction pass, since there was only one track going through the tunnel. It was established in 1931 at the time of the inauguration of the Joetsu Line, and named Tsuchitaru Signal Station (土樽信号場) after the village where it was located (in the town of Yuzawa); it was “promoted” to full station status (駅・eki) in 1941, so people could get off there and make the quick three-minute walk over to the nearby ski slopes.

You might think this name means “earth-cask” or something like that, but actually, as with Nanadaru, this taru refers to a waterfall, and the tsuchi indicates the saltpeter found in this area in times past. So the name could be rendered as “Saltpeter Falls”.

We should also note that a 信号所・shingō-sho[jo・signal stop is not just some signal out in the middle of nowhere; it is a facility which in addition to signals has switches, someone assigned to operate those switches, and a little building for them to sit in. It is thus more common to call them signal stations. They can be thought of as little train stations without passenger facilities. The official terminology would be 信号場・shingōjō. There are about 200 of them throughout Japan. Two-thirds of them have the main purpose of letting trains pass, like the one at Tsuchitaru.

But if this was a mere signal stop, or signal station, then why would the girl sitting across from Shimamura have called out 駅長さあん・ekichō-saan・"station master”, a

verbalization which by the way Seidensticker inexplicably omits completely? Wouldn’t an 駅長・ekichō・station master be found only at a full-fledged 駅・eki・station? The answer, and it is relevant for the translation of the upcoming sentences of the book, is that due to the importance of signal stations—incorrect operation of the switch could result in tragedy—they were staffed with skilled, senior employees who might have the title of station master (駅長格) without the actual role. Anyway, your homework for the day is to suggest how to represent the extra あ・a sound in 駅長さあん・ekichō-saan in English. Did Seidensticker leave this out because he couldn’t figure that out?

In the next post, we will take a look at the third sentence of Snow Country about the train stopping at the signal station, and think about how translators should think about order and how they can deal with it.