I was browsing my social feeds and what should pop up but an upcoming device that you attach to your toilet to analyze your urine and report on your nutrition and health. This is from the company called Withings, famous for its digital bathroom scales and blood pressure monitors.

It’s the U-Scan Nutrio, the first toilet plug-in urine scanner! It detects ketone levels, and vitamin C levels, and bio-acidity, and hydrostatus, whatever that is. You will have to install it on the front toilet rim in a position where it actually sits in the, uhh, you know, stream. Make sure to replace the cartridge after 20 scans, eww. The results are sent over WiFi to the Withings app. Can’t wait!

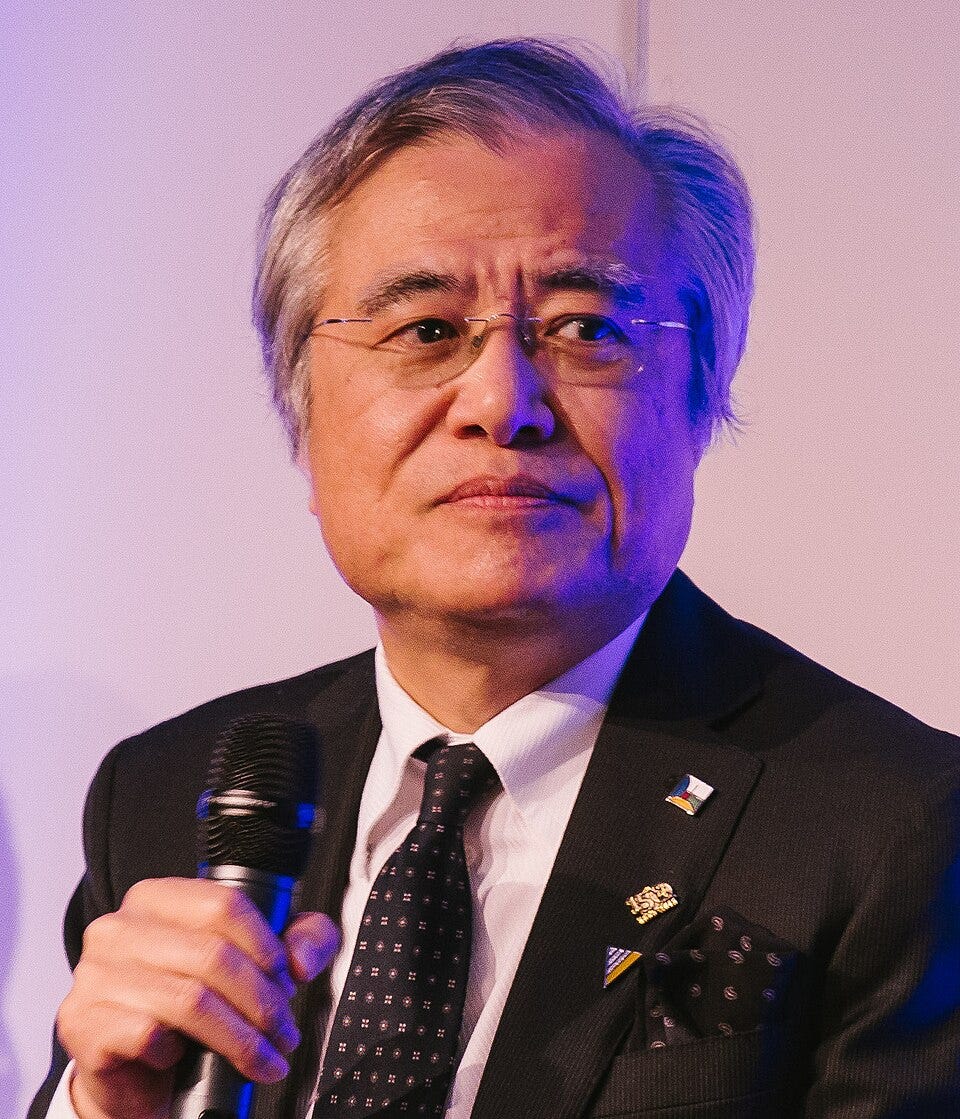

When I heard of this, I immediately thought back more than thirty years when I heard the exact same idea from Dr. Ken Sakamura, the legendary Tokyo University professor who founded the TRON project.

Here's a quote from him in an interview on the occasion of TRON’s 30th anniversary about ten years ago:

When I created the first TRON smart home (電脳住宅) in 1989, I said we should think about housing for the elderly. I was working with TOTO and told them to attach a blood pressure monitor to the toilet. And also build in the kind of automated urine scanning device they have in doctor’s offices into the toilet, connected to the family doctor over a communications line, letting you automatically take your blood pressure and analyze your urine every time you went to the bathroom, but they didn’t like my idea of storing the data, back then. But we went ahead and made it. We made it, but there was no internet, and when we asked NTT they came up with an ridiculously expensive thing involving dedicated lines to hospitals, so it failed due to cost reasons. Now we could do it with no problems whatsoever.

He was certainly way ahead of the curve here. I’m not aware of the degree of detail Sakamura had in mind for the urine sensor, like whether the sensor would have to be “in the stream”. But the idea got quite a bit of attention, although I don’t think it ever even reached the prototype stage.

The smart toilet was just one small idea of the huge number that Sakamura’s fertile mind came up with. He had an overarching vision of an all-encompassing computing architecture. It ranged from microprocessor design, to a real-time OS like they use in cars, to a desktop OS, to a networking OS, to a coding system for kanji, to peripherals like keyboards, an object interaction model, and even entire smart houses. His smart toilet was not an isolated idea: the urine sensor would be a node in his global mesh of intelligent objects, all tied together via the TRON protocol.

His detractors jokingly called this the 日の丸OS (hinomaru OS), trying to paint it as a jingoistic, nationalistic initiative. But that’s actually exactly what (I think) it was supposed to be: a “Japanese computing environment”. I can’t say that Sakamura ever articulated this precise concept. Or had even necessarily thought through what a “Japanese computing environment” would entail. But that is unmistakably what it was.

This publication is supposed to be about the Japanese language. In that context of course we also talk about Japanese culture. But today let me depart a bit from my usual topics and talk about TRON, in which I myself had a small involvement. I was a visiting research fellow studying in the so-called 坂村研究室 (Sakamura-ken) in the 情報科学部 (Department of Information Science) at Todai. I designed some elements for B-TRON, the desktop operating system, including a dynamic component to translate documents and even entire applications between languages in real time. Never mind that we were still decades away from the technology that would be needed to make that happen.

But let us go back to the topic of what a “Japanese computing environment” would be, assuming that’s what Sakamura was trying to design. It would have to be more than a special keyboard designed for small Japanese hands (yes, TRON had its own keyboard, and yes, it is said it was designed for smaller hands). I have no idea how this was supposed to work, but it looks cool. The layout for English is Dvorak. Note the tablet-like area; Sakamura hated mice and insisted on pen-based input.

And it would have to be more than a kanji encoding (called TRON Code), which predated Unicode. It would have to do more than meet the needs of an aging society, which was one of the drivers of Sakamura’s notion of home automation. No, it would need to be “Japanese” in two high-level respects: the technology architecture, and the approach to rolling it out and popularizing it.

In terms of the technology architecture, one notable feature of TRON was its jisshin/kashin model. A jisshin (実身) was an (addressable) object itself; a kashin (仮身) was a sort of pointer to it, an alias, a link, a smart shortcut. A document in the TRON version of a word processing app could include kashin just like today an HTML document could include a link to other HTML documents. But the difference was that the relationship between all the documents and their pointers was managed by a specialized file system, which allowed kashin (links) to include metadata, such as the nature of the pointing relationship—-a kind of semantic functionality that many have attempted to layer on top of HTML (remember the “semantic web”?) but never really succeeded.

This jisshin/kashin model is strongly reminiscent of the distinction that is key to Japanese culture: front/back omote/ura, which we discussed in detail here. The jisshin is the ura, the essential being of something; the kashin is the omote, all the ways it exposes and presents itself in different contexts.

In the TRON architecture, all these jisshin (we would call them “files”, except that even fragments of documents are independently addressable, and can even have their own kashin pointing to them), are not organized in anything we would recognize as a “file system” with hierarchical folders and directories. They are instead stored essentially in a huge soup, where they can be found and referenced by their connections to other items. The structure is not imposed a priori, top-down; it’s implied by the relationships between objects. There is sort of a “left-branching” concept at work here; the details—-the individual objects—-come first, and the big picture comes last.

So Sakamura, consciously or not, can be thought of as having invented an object architecture which respected Japanese cultural principles of ura/omote and left-branchiness.

Unfortunately, as we will see in a follow-up post, whether because or this or in spite of it, and also due to political and other factors at play, TRON never really gained traction.

It is a well-known principle of software engineering that software architectures reflect the structure of the software organization than create them. Here a similar principle is at work: computing architectures reflect aspects of the cultures that create them.

We must have crossed paths. I tried hard to get my bosses at Apple to work with him back in the day. I wonder what became of the TRON house.